Wieliczka holds an underground secret: pure beauty. Here’s what it’s like to go deep beneath the earth, complete with tips for visiting the salt mines near Krakow.

Tips for Visiting the Salt Mines near Krakow

“Once we start, I will not be able to talk to you. And you will not be able to turn back.”

The man stands cloaked in a long charcoal jacket, blowing on his hands to keep warm. For a giant-sized man, he uses a soft voice.

“Are you ready?” he asks again.

I figure I’m as ready as I’ll ever be to climb down 100 metres beneath the earth. And so, we go.

Koplania Soli – The Wieliczka Salt Mines

Automated instructions blast in English, German and Polish, an official steps aside and we begin the descent, down, down, down into Kopalnia Soli: Wieliczka’s salt mines and a World Heritage Site to boot.

Work began here back in the 13th century and the mines have functioned ever since, through landslides, floods, the Nazi invasion and communist Russia. The real story, however, started 20 million years ago, when the sea covered this part of Poland, leaving behind buried treasure in the form of sodium chloride.

There’s plenty of time to contemplate history, geology and chemistry as the creaking wooden staircase goes on and on, round and around, down and down. Over a million people visit each year and it’s difficult to see how the flimsy stairs cope. We traipse through makeshift corridors, stooped in the gloom of some sparse electric bulbs.

So far, Wieliczka is behaving as any mine should. It’s dark, dirty and dangerous.

St Anthony’s Chapel

St Anthony’s Chapel changes all that. Carved by the miners into the lead-like rock salt, this fairytale world glistens under the quiet, soft light. Life-size figures sparkle in the silence.

As with all good fairytales, we meet a princess. According to legend, when Princess Kinga of Hungary became betrothed to King Boleslaw the Bashful around 700 years ago, she threw her engagement ring into Hungary’s salt mines.

What may sound like a temper tantrum instead guided the Princess to the salt supplies in her adopted country of Poland. When drilling started in Wieliczka, miners found not only salt but the engagement ring itself.

King Kazimierz the Great & Copernicus

Our next royal encounter is a little more sedate: a traditional bust of King Kazimierz the Great, Krakow’s most famous ruler, whose name still describes the city’s revived Jewish Quarter. Next up was the great scientist, Copernicus, the first man to stare into the heavens and calculate that the Earth was not actually the centre of the universe after all.

This deep beneath the earth, it’s hard to remember that the stars even exist. And humbling to learn that Copernicus himself visited Wieliczka as a student in the 15th century.

Natural Salt Art

Down in the mine, we won’t find stars. Instead, salt decorates the ceiling. Although raw rock salt looks a mottled, granite grey, when combined with water, the crystals dissolve and then reform in tangled, fragile formations.

“We call them spaghetti and cauliflowers,” says Christopher, catching my eye. “For obvious reasons.”

I reach out and touch a “cauliflower.” It feels tough, a coarse resilience grazes my fingers. Rather like Wieliczka itself: deceptively beautiful, incredibly tough.

The Salt Mines Museum

In the museum section, plastic men with hooded faces labour alongside horses, axes and carts. These everyday workers, toiling out of sight of the world, conceived sculptures so impressive that the rest of the world still falls through the earth to see them, some earning a statue of themselves in return. Copernicus, Goethe, local lad Pope John-Paul II. Even a merry dwarf who promises instant fertility if you kiss him on the nose.

The Chapel of St Kinga

Yet all of this fades into the shadows at the grand finale: the Chapel of St Kinga.

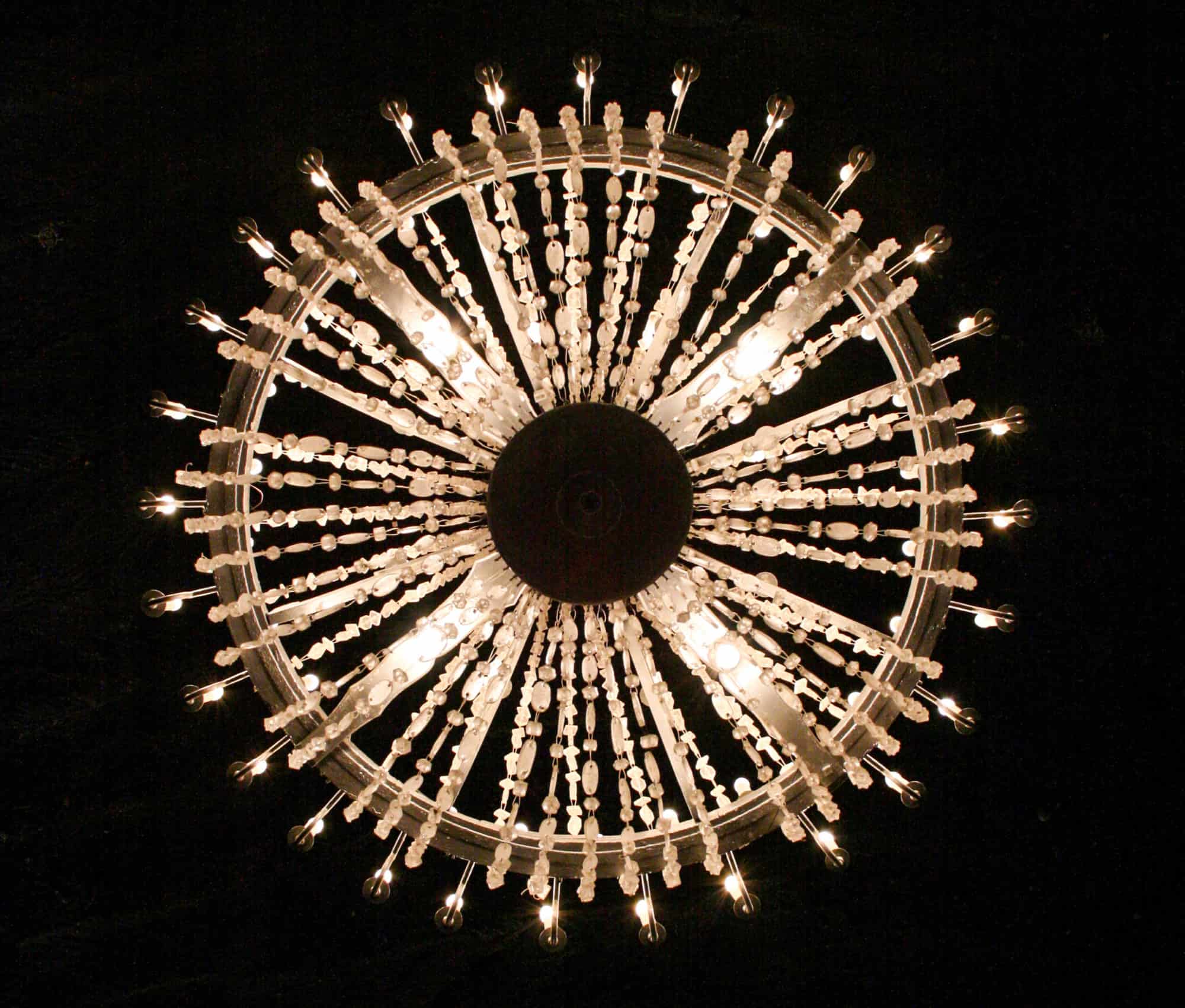

Salt-diamond light fills this 23 000 cubic metre cavern, with each chandelier made from purified, clear salt. Religious panoramas cover the walls and illuminated rose salt glows as the heart of Jesus and then characterises God himself.

Back to the Surface

The tour ends with a heart-choking ride to the surface in a caged rocket of a lift. But before I leave, I catch a glimpse of Wieliczka’s forgotten heroes.

Lamps in place, pick-axes slung over their shoulders, two miners smile at each other, forever frozen in salt.

They seem to be sharing a joke. And perhaps that’s the last of Wieliczka’s great secrets.

Tips for Visiting the Salt Mines Near Krakow: Practical Information

- Wear sturdy, non-slip shoes. The ground is uneven and steep in places.

- Wear a cardigan or bring a light jacket. It’s considerably cooler underground than it is on the surface.

- You have to visit with a guide but you can turn up at the door and buy tickets there. Alternatively, tours for tourists leave frequently from Krakow.

- The route is one way and visiting takes several hours.

- Avoid if you don’t like enclosed spaces, darkness, or climbing a lot of steps!

- Not suitable for very young children.

- Check up to date entry information for the salt mines here.

I like that first photo. Imagine it would feel like walking down to Hades.

Luckily, we didn’t have to walk back up!

Unbelievable!!!

And yet hardly anyone knows anything about them…Amazing.

I love learning about places I’ve never been to before – and a world heritage site in fact! A Hungarian fairy tale is always a bonus. Nice pictures as always.

Well, quite! A story’s not a story unless there’s a princess lurking around. Thanks for the kind words.