Pre-Columbian Art in Ecuador and the Surprising Question It Asks

Christopher Colombus. One nation’s hero, one continent’s despair. Endless generations of schoolyard amusement when English speakers realised that his real name was Colon.

But I want to move past him for now, and focus instead on the art scene in Ecuador, the one that flourished at around 2850 metres before the Spaniards arrived.

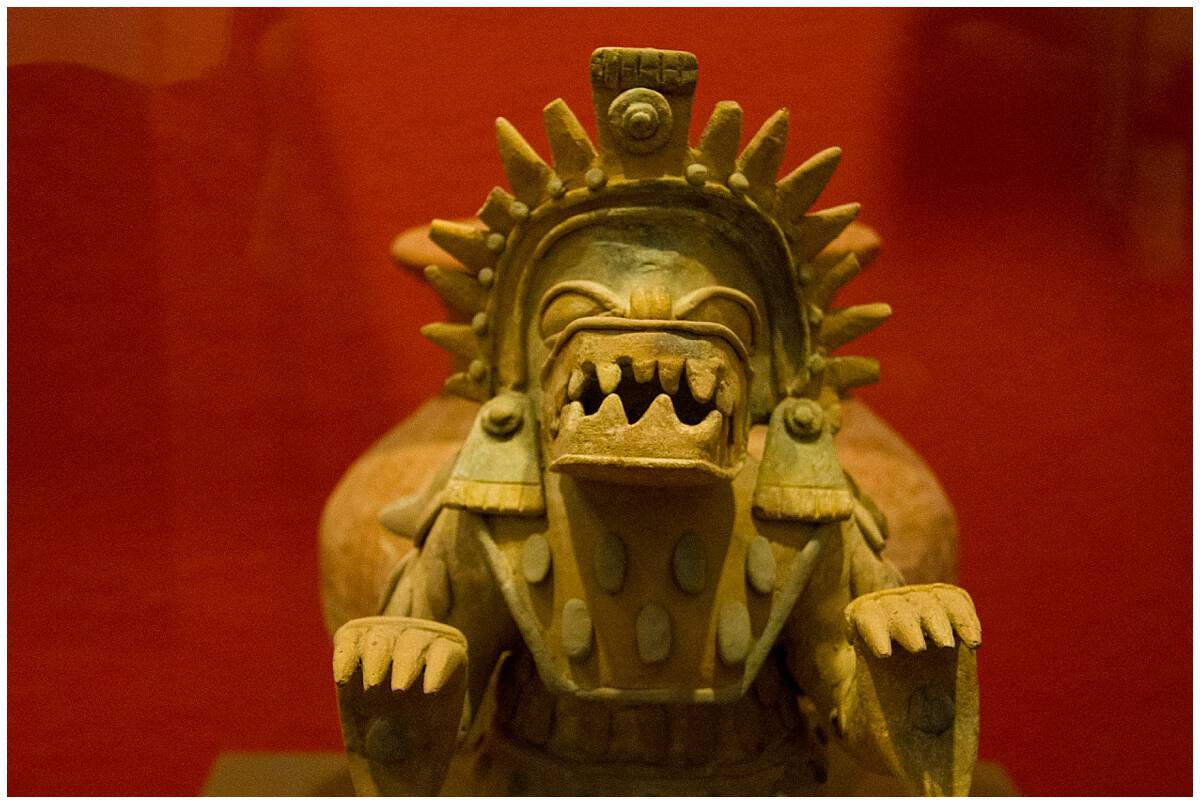

Because as it turns out, there is a lot. Punchy, pithy, puerile and pretty – and absolutely plenty of it.

Inside the Casa del Alabado

Oddly, though, at least through my newcomer’s eyes, the museum that houses it near defines itself by what it is not: its tagline is pre-Columbian art and it lives in a colonial era mansion, all lush and beautiful and spilling over with tumbling green leaves and atmospheric terracotta light. Which is why I was reminded of the tight-wearing gentleman funded by Spain to begin with.

In the Casa del Alabado, the contents are plentiful, my time here short. My knowledge shamefully slight.

Yet something is better than nothing, and so I look and photograph and read and do my best to translate.

I’m reminded, of course, that the nation states we know today did not exist “back then.” In the grand scale of human activity, they’re a short-lived phenomenon with other tribes and societies and methods of organisation stretching into a fluid patchwork quilt of love and belonging and blood the world over.

Today’s Ecuador is no different.

Ecuador: A Country of Mixed Cultures

The Casa houses art from no fewer than 15 different societies: the chapo, puruha, jama coaque, cosanga pazuelo, carchi pasto and more. The only one I can honestly say I recognise is built from four small letters: inca. The people behind the jagged iconic peaks of Macchu Picchu.

Today’s Ecuador encompasses many different landscapes and it’s clear that people adapted to the conditions in which they lived.

I’ve walked around modern and colonial Quito, high in the Andes at 9350 feet. I’ve cycled through the air in the cloudforests of the Andean foothills, and crossed the equator to get there. I’ve swum around the Galapagos, spotting turtles, seals and blue-footed boobies.

But there’s still so much left of the country, to explore, to find, to see.

South and Central American Similarities

Yet even to the (desperately) untrained eye, there are similarities here to see. Differences, yes, but also patterns, similarities, trends.

The first is the characterful clay character, smurf size and with various pieces added on, like several I’d found in Mexico.

The second was the preponderance of geometric lines, the simplistic style seen in the Nazca lines in Peru.

And thirdly, of course, was the gold – and with it the foibles of mankind laid bare.

The Meaning of Gold

I’d always been intrigued about the stories of cities of gold since watching cartoons as a child. When the Spanish arrived in Inca Peru, they found gardens filled with statues encrusted with gems and made of pure gold.

In the high city of Colombia’s Bogota, the Museo del Oro speaks of nothing but the stories of gold.

But what is gold really and what is its point? It’s decorative, clearly, and that’s about it.

Except, of course, to the conquistadores, it meant power. They stripped and shipped the metal back to Europe, making Spain the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world at the time.

That so many pre-Columbian cultures used it for decoration seems far more sensible than locking it in a vault and never letting it see the light.

Yet only a few centuries later, this strange substance set the world mad again as prospectors risked all they had to race into the bloodied rivers and plains of the American Wild West.

What Do We Value Today?

And what do we value today?

Art? Gold? Numbers? Faith? A little bit of all of it, swirling around each other?

And, perhaps most intriguingly, what do you think the people of the future will line up to see to learn a little about our lives?

More From Ecuador

- The oldest market in Quito has tales to tell

- Why the cloud forests of Ecuador matter to us all

- What do the words Galapagos mean?

Top Tip! Work out what to wear in the jungle with this handy guide.

I do wonder what we’ll leave behind given that so many of our artifacts now exist virtually — what will remain and what will disappear when the technology is no longer usable? What will the gaps be?

This is a lovely introduction — like you, my knowledge is so slight; it’s hard to understand things without enough context, especially when something — a culture, a history — is so complex. Though I suppose that is why we travel.

Yes, that’s certainly a large part of why we travel (or at least why I do.) Travel always seems to confront how little it is that I actually know! But it acts as a springboard and I always learn another piece of the jigsaw on each trip (to completely muddle my metaphors!)

I rather imagine that what we’ll leave behind will be our architecture (if it lasts) and, sadly, the plastic in our landfill sites. I’m not sure what will happen to our art, literature, social interaction and so on – as you say, so much is virtual. But perhaps in the future someone will find a way of archiving and sifting through all that?

If so, hello future person! And sorry about all that plastic landfill…

One thing I always think about is the loss of letters — so much of what we know about a lot of great writers, artists, historical figures, etc. is through their letters. As an art form, that’s vanishing. It’s very specific and not exactly what you’re writing about here, but it’s also something that’s been important to me as a writer myself (I’m currently reading the letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald). There will be physical landmarks left behind, but some of the things that might help the future understand those landmarks might be tricky. Though I suppose that the future (yes, sorry about those landfills) will adjust their research and figure it out.

You’re giving me a lot to think about :)

Yes, true, and very timely as more letters from Sir Isaac Newton have just been discovered that shed light on the personal aspects of his life. Though l do remember feeling a little uneasy when reading letters from Winston Churchill as a boy to a relative at Blenheim Palace. I felt a little voyeuristic perhaps? Or perhaps I just worried about what my letters to my mother would have looked like and whether or not I would have wanted the world to read them (!) But, yes, letters as an art form, as a deeply thought out process – that concept has almost disappeared already. An alternative future vision will be texts and emails… LOL (!)

It does feel a bit voyeuristic reading letters and journals, though I will admit I feel lucky to do so (is it any different from viewing petroglyphs? Maybe?)

Interestingly, there was a recent article at the Atlantic that’s kind of talking about some of this. I thought you might find it interesting. Not sure if the link will register as spam, but the title is: Future Historians Probably Won’t Understand Our Internet, and That’s Okay. I wanted to share it with you!

With petroglyphs (and blogs, when it comes to it!) the idea that anyone could see it is implied during its creation. Whereas, with a letter, there is perhaps the assumption of privacy. (Would emails be the same?) I suppose public figures may perhaps write their diaries and journals with a view to them being published… There was an interesting section on this at the Anne Frank museum in Amsterdam around whether or not the diary should have been published, whether her father was right to remove some of the most intimate parts, whether subsequent publishers did the right thing by adding them back in…

That’s a really great article – I’ll put the link here for other readers (think you’re right, it would have snagged the spam filter!)

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/12/it-might-be-impossible-for-future-historians-to-understand-our-internet/547463/

Thanks so much for the really interesting thoughts and discussion.